Thursday, December 28, 2006

Travel Article on NYT

Many thanks to Satiprasad who pointed out this travel story on Bangladesh in NY Times. Nice to get the coverage.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Which Language to Write

I was reading writer Mahmud Rahman's blog, where he discusses the language one chooses to write in, and its relationship to one's mother tongue. He approaches the issue from a writer's point of view - that is, the special problems that the writer faces when his or her mother tongue is different from the language that he or she chooses to write in. A fascinating topic.

That's a writer's dilemma, of course, but every time I write something in English - that, say, gets published in the Daily Star - something else bugs me: that the vast majority of educated Bangladeshis will not be able to read what I have written because they are educated in Bangla.

So for me, the big question is: who is the audience I write for? That is the basic question that I think many creative people must grapple with. In the subcontinent, Mulk Raj Anand and R. K. Narayan were the two early successful novelists in English - but look at what happened to Michael Madhusudan Dutta.

If you are a creative person, perhaps you have some thoughts? I have heard arguments that Satyajit Ray's Pather Pachali was really meant for a Western audience. But I have also read about Ray vehemently denying it. More importantly, can one argue that there ought to be a moral bias towards a particular type of audience the work of art is created for?

I have no confusion about who I write on this blog for. It is meant for our friends in the US, as well as anyone else, who is interested in the experiences of a returning NRB. As such, English is the way to go. But I also feel some loss at not being able to write as fluently in Bangla as I once did. My Bangla, as they say, "aRoshTo hoye gechhey." Something I want to fix in the future, definitely.

That's a writer's dilemma, of course, but every time I write something in English - that, say, gets published in the Daily Star - something else bugs me: that the vast majority of educated Bangladeshis will not be able to read what I have written because they are educated in Bangla.

So for me, the big question is: who is the audience I write for? That is the basic question that I think many creative people must grapple with. In the subcontinent, Mulk Raj Anand and R. K. Narayan were the two early successful novelists in English - but look at what happened to Michael Madhusudan Dutta.

If you are a creative person, perhaps you have some thoughts? I have heard arguments that Satyajit Ray's Pather Pachali was really meant for a Western audience. But I have also read about Ray vehemently denying it. More importantly, can one argue that there ought to be a moral bias towards a particular type of audience the work of art is created for?

I have no confusion about who I write on this blog for. It is meant for our friends in the US, as well as anyone else, who is interested in the experiences of a returning NRB. As such, English is the way to go. But I also feel some loss at not being able to write as fluently in Bangla as I once did. My Bangla, as they say, "aRoshTo hoye gechhey." Something I want to fix in the future, definitely.

Saturday, December 16, 2006

Monday, December 11, 2006

Baikka Beel (Photos)

Baikka Beel is a wildlife sanctuary in the Hail Haor wetlands near Srimongol. It is a USAID-funded project. I bicycled there yesterday. Here are some pictures.

The sign on the main MoulviBazar-Srimongol road is to your right if you are coming from MB, about 0.5 km past Bhairabganj Bazar:

On the road I ran into fishermen returning from the haor with fish...

... as well as water buffaloes, whose milk is rich and flavorful...

... not to mention grandma who was out shopping with granddaughter...

...but this horseman was a surprise.

After about an hour of cycling from the main road, there was this explanatory sign...

...and an observation tower with incredible views from the top.

On the tower, Ujjol - one of the caretakers - points out some birds...

... of which there were thousands...

...and thousands.

Another view from the tower...

As I started back I saw the field was full of cobwebs reflecting morning light.

An excellent morning of exploration. My thanks to the sponsors and organizers of this project, which provides sanctuary for 98 types of fish and 160 types of birds. I will certainly visit it again, Inshallah.

The sign on the main MoulviBazar-Srimongol road is to your right if you are coming from MB, about 0.5 km past Bhairabganj Bazar:

On the road I ran into fishermen returning from the haor with fish...

... as well as water buffaloes, whose milk is rich and flavorful...

... not to mention grandma who was out shopping with granddaughter...

...but this horseman was a surprise.

After about an hour of cycling from the main road, there was this explanatory sign...

...and an observation tower with incredible views from the top.

On the tower, Ujjol - one of the caretakers - points out some birds...

... of which there were thousands...

...and thousands.

Another view from the tower...

As I started back I saw the field was full of cobwebs reflecting morning light.

An excellent morning of exploration. My thanks to the sponsors and organizers of this project, which provides sanctuary for 98 types of fish and 160 types of birds. I will certainly visit it again, Inshallah.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

What Does Catman Do?

Years ago when I was new to Unix, I was having trouble understanding the man page for "catman" command. So I asked another engineer, Steve, "What does catman do?" and he said, "It is the capital of Nepal." Heh heh.

Last week I visited Kathmandu for the first time to accompany my son's school basketball team - my son plays in that team - competing in a regional tournament. They won the championship competing against schools from Delhi, Kathmandu, Colombo, Bombay, Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad and Murree. Congrats Tigers!

Kathmandu was interesting, but also raised troubling questions. They have a huge tourism industry, but where do the tourist dollars go? Talking to some locals, I got the impression the people are very poor. But incredibly nice, friendly and they liked Bangladesh a lot. A lawyer I met during lunch at a local hole-in-the-wall told me that the years of Maoist insurgency had really drained the economy.

I was in KTM the whole time, but if you go on a trek, for $30-$50/day/person you get guide+porter, lodging at "tea houses" and food. What kind of food? The guide shows you a menu and you choose what you want to eat and they cook or order it for you. Wow! Luxury in the mountains. Far cry from the gorp-and-freeze-dried sustenance I endured while backpacking in the Sierra Nevada.

Here is what really bugs me. So these mountains are their country. Yet, the poor Nepalese do the grunt work while foreign tourists explore the mountains like lords. Hardly seems fair, does it?

Last week I visited Kathmandu for the first time to accompany my son's school basketball team - my son plays in that team - competing in a regional tournament. They won the championship competing against schools from Delhi, Kathmandu, Colombo, Bombay, Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad and Murree. Congrats Tigers!

Kathmandu was interesting, but also raised troubling questions. They have a huge tourism industry, but where do the tourist dollars go? Talking to some locals, I got the impression the people are very poor. But incredibly nice, friendly and they liked Bangladesh a lot. A lawyer I met during lunch at a local hole-in-the-wall told me that the years of Maoist insurgency had really drained the economy.

I was in KTM the whole time, but if you go on a trek, for $30-$50/day/person you get guide+porter, lodging at "tea houses" and food. What kind of food? The guide shows you a menu and you choose what you want to eat and they cook or order it for you. Wow! Luxury in the mountains. Far cry from the gorp-and-freeze-dried sustenance I endured while backpacking in the Sierra Nevada.

Here is what really bugs me. So these mountains are their country. Yet, the poor Nepalese do the grunt work while foreign tourists explore the mountains like lords. Hardly seems fair, does it?

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

A Book I Await

The Golden Age by Tahmima Anam, due out in January from John Murray, promises to be a rich, interesting novel with the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War as background. It is attracting positive press coverage already. The Guardian called her "a major new talent." Excerpt to appear in January's Granta. Wow!

http://books.guardian.co.uk/news/articles/0,,1957394,00.html

http://books.guardian.co.uk/news/articles/0,,1957394,00.html

Sign Language (photos)

Thursday, November 23, 2006

In the Land of Cup and Lip: Becoming a Bangladeshi Again

[A slightly different version of this essay appears in The Daily Star Weekend Magazine today. Notes for non-Bengali readers follow the essay.]

After living 30 years abroad, I have returned to Bangladesh. I am re-learning how to live in my native land. While rediscovering many sights, sounds and tastes from my childhood, I am also evolving a new way of living that echoes the rhythm of life here.

Take the seasons for example. Sure, I knew Bangladesh has six, but over the years I had grown clueless about their bounties. Not any more. As Grishho (summer) approaches, all my thoughts turn to Rajshahi mangoes. Water covering miles of fields in Borsha (rainy season) does not unsettle me because in Hemonto (late autumn) I will see the same fields glowing golden with paddyfields. Shorot (early autumn) brings Shaplas of more colors than I had imagined. In Sheet (winter), during an orange-green sunset, I watch the fog roll into the tea garden hills. As Boshonto (spring) emerges from winter, bright orange Krishnochuras set the sky aflame.

I fathom nature's mysteries with patience, but man-made ones stump me. Why do rickshaws have two brake-handles but only one works? What are those towels on the back of officers' chairs for? Why is a job titled "Senior Assistant" when those words mean "Senior Junior?" Why is personal integrity so rare that we point out so-and-so is an "honest" officer as if they were a rare Doodhraj bird (paradise flycatcher)? When I need directions, why does one who does not know insist on being helpful and point me the wrong way? Why do cars blink hazard lights when they are crossing an intersection? And what is a "Gatelock" bus?

Of life's uncertainties, Shakespeare said, "Many a slip 'twixt cup and lip." Living in Bangladesh, the land of cup and lip, I must accord uncertainty its due stature. Making a weekend plan for a short trip out of town? A hartal strikes. Going to an important business meeting? Sorry, my counterpart's aunt died and he is absent from office. Flying overseas tomorrow? At 8pm the night before my travel agent carrying my ticket is stuck in traffic.

With growing uncertainty comes less privacy. At a government office a visitor inadvertently entertains us by discussing private business with the officer in front of five other visitors like me. Back in my own office, a one-on-one discussion regarding an employee's performance issues is interrupted several times as people walk in for various reasons.

I quickly learn to be mistrustful of unexpected privacy. Choosing to walk on the right side of a bridge because everyone else is on the left, I soon discover the reason for my privacy: this side harbors a hidden garbage dump emitting noxious stench.

Following other pedestrians’ footsteps, I compulsively avoid climbing pedestrian overpasses when crossing the road. If I need to cross the road, I will brave oncoming traffic, jump over traffic islands, and risk getting my jeans ripped by barbed wires placed precisely to discourage jaywalkers like me. That overpass is for sissies, not Real Bangladeshis.

Unexpected new words or phrases tell me that even the language has changed. Some, like Bhasha Shoinik referring to those who fought in the Language Movement of the 1950s and 60s, are powerful additions. Shopkeepers seeking class insist their goods, once shosta (cheap), are now shasroyee (inexpensive). But who let irritations like aalga pechail and kora mishTi into this sweet language of mine? Best of all, I hear villagers say Bangla to mean Bangladeshi (“He is a Bangla”), silencing the tedious "Bangladeshi" vs "Bengali" arguments.

Fears that dogged me during the early days of my return slowly recede. The risk of dengue from a mosquito bite sustained during the day no longer keeps me awake at night. Nor do I hunt down the blood-engorged mosquito to check for white stripes as I once did, because this knowledge is utterly useless a posteriori. Food adulteration, traffic accidents, pollution and noise - these are all reduced from unacceptable to mere nuisance.

While fears reduce, death becomes a bigger part of life. I find that we Bangladeshis have trouble letting go of our dead, starting with our two long gone political leaders who, after so many years, still tower over national politics. The newspapers are full of notices of not just some prominent person who recently passed away, but also of 10th, 15th or even the 20th anniversary of important peoples' death! Many of these influential people achieved much because of their focus on the present. Yet, here we are, harping on the past, invoking their memory for sentimental - or worse, manipulative - reasons.

In a bid to shake off morbid thoughts, I explore the parks and gardens. I observe the elegance of the Bulbuli as it weaves in and out of the flowers, and marvel at the resourceful Shalik consistently managing to find food on the roadside. I watch with suspense as a Cheel dives into the water to grab lunch, and my heart jumps with the Fingey as it flicks its long V-shaped tail swinging on electric wires and then swoosh! zips away. I feel – however fleetingly - the profundity of Jibananda Das's words:

"You all can go wherever you want

I will stay right here in Bangla".

The sweetest rewards come unexpectedly. Biting into a LoTkon fruit after thirty years, my mind is flooded with childhood memories, like Proust's character Swann experienced when he tasted a madeleine cookie in "Remembrance of Things Past."

I gauge my progress towards my goal during chance encounters with the locals. Like the time when I am bicycling through a village in Rupganj area. A boy, barely ten, stops me, points to a tall Kamranga tree full of ripe juicy fruit, and offers to climb it and pick some, free of charge. "Want to try it, sir, it is very sweet", he asks me. I had forgotten how unbelievably hospitable, friendly and generous Bangladeshi villagers are. I realize that attaining this level of being Bangladeshi will be tough.

[Notes for non-Bangladeshi readers:

1. Bangladesh has 6 seasons: Summer, Rainy Season, Early Fall, Late Fall, Winter and Spring. In Bengali these are Grishho, Borsha, Shorot, Hemonto, Sheet, Boshonto. The language is Bengali (aka Bangla.)

2. Rajshahi in northern Bangladesh is famous for its sweet mangoes.

3. Shapla, a water-lily, is the national flower of Bangladesh.

4. Bangladeshi rickshaws have two brake handles but only one is attached to a (front) brake. There is no brake at the rear.

5. A hartal is political protest that shuts down shops and most traffic for the day. Offices usually remain open.

6. The Language Movement, from the 1950s, was a people’s movement in Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) to promote Bengali and resist the adoption of Urdu (spoken only in West Pakistan) as the national language.

7. Aalga Pechail means “unnecessary complicated talk” and Kora Misti means “very sweet” (used by fruitsellers.)

8. Shalik, bulbul, fingey and cheel are birds of sturnidae, nightingale, drongo and kite families.

9. Jibananda Das, a Bengali poet, is best-known for his celebration of natural beauty of the region.

10. You can reach Rupganj in an hour of bicycling from Dhaka’s diplomatic zone.

11. Kamranga is starfruit. LoTkon is a local fruit, intensely tangy with a nice flavor.

After living 30 years abroad, I have returned to Bangladesh. I am re-learning how to live in my native land. While rediscovering many sights, sounds and tastes from my childhood, I am also evolving a new way of living that echoes the rhythm of life here.

Take the seasons for example. Sure, I knew Bangladesh has six, but over the years I had grown clueless about their bounties. Not any more. As Grishho (summer) approaches, all my thoughts turn to Rajshahi mangoes. Water covering miles of fields in Borsha (rainy season) does not unsettle me because in Hemonto (late autumn) I will see the same fields glowing golden with paddyfields. Shorot (early autumn) brings Shaplas of more colors than I had imagined. In Sheet (winter), during an orange-green sunset, I watch the fog roll into the tea garden hills. As Boshonto (spring) emerges from winter, bright orange Krishnochuras set the sky aflame.

I fathom nature's mysteries with patience, but man-made ones stump me. Why do rickshaws have two brake-handles but only one works? What are those towels on the back of officers' chairs for? Why is a job titled "Senior Assistant" when those words mean "Senior Junior?" Why is personal integrity so rare that we point out so-and-so is an "honest" officer as if they were a rare Doodhraj bird (paradise flycatcher)? When I need directions, why does one who does not know insist on being helpful and point me the wrong way? Why do cars blink hazard lights when they are crossing an intersection? And what is a "Gatelock" bus?

Of life's uncertainties, Shakespeare said, "Many a slip 'twixt cup and lip." Living in Bangladesh, the land of cup and lip, I must accord uncertainty its due stature. Making a weekend plan for a short trip out of town? A hartal strikes. Going to an important business meeting? Sorry, my counterpart's aunt died and he is absent from office. Flying overseas tomorrow? At 8pm the night before my travel agent carrying my ticket is stuck in traffic.

With growing uncertainty comes less privacy. At a government office a visitor inadvertently entertains us by discussing private business with the officer in front of five other visitors like me. Back in my own office, a one-on-one discussion regarding an employee's performance issues is interrupted several times as people walk in for various reasons.

I quickly learn to be mistrustful of unexpected privacy. Choosing to walk on the right side of a bridge because everyone else is on the left, I soon discover the reason for my privacy: this side harbors a hidden garbage dump emitting noxious stench.

Following other pedestrians’ footsteps, I compulsively avoid climbing pedestrian overpasses when crossing the road. If I need to cross the road, I will brave oncoming traffic, jump over traffic islands, and risk getting my jeans ripped by barbed wires placed precisely to discourage jaywalkers like me. That overpass is for sissies, not Real Bangladeshis.

Unexpected new words or phrases tell me that even the language has changed. Some, like Bhasha Shoinik referring to those who fought in the Language Movement of the 1950s and 60s, are powerful additions. Shopkeepers seeking class insist their goods, once shosta (cheap), are now shasroyee (inexpensive). But who let irritations like aalga pechail and kora mishTi into this sweet language of mine? Best of all, I hear villagers say Bangla to mean Bangladeshi (“He is a Bangla”), silencing the tedious "Bangladeshi" vs "Bengali" arguments.

Fears that dogged me during the early days of my return slowly recede. The risk of dengue from a mosquito bite sustained during the day no longer keeps me awake at night. Nor do I hunt down the blood-engorged mosquito to check for white stripes as I once did, because this knowledge is utterly useless a posteriori. Food adulteration, traffic accidents, pollution and noise - these are all reduced from unacceptable to mere nuisance.

While fears reduce, death becomes a bigger part of life. I find that we Bangladeshis have trouble letting go of our dead, starting with our two long gone political leaders who, after so many years, still tower over national politics. The newspapers are full of notices of not just some prominent person who recently passed away, but also of 10th, 15th or even the 20th anniversary of important peoples' death! Many of these influential people achieved much because of their focus on the present. Yet, here we are, harping on the past, invoking their memory for sentimental - or worse, manipulative - reasons.

In a bid to shake off morbid thoughts, I explore the parks and gardens. I observe the elegance of the Bulbuli as it weaves in and out of the flowers, and marvel at the resourceful Shalik consistently managing to find food on the roadside. I watch with suspense as a Cheel dives into the water to grab lunch, and my heart jumps with the Fingey as it flicks its long V-shaped tail swinging on electric wires and then swoosh! zips away. I feel – however fleetingly - the profundity of Jibananda Das's words:

"You all can go wherever you want

I will stay right here in Bangla".

The sweetest rewards come unexpectedly. Biting into a LoTkon fruit after thirty years, my mind is flooded with childhood memories, like Proust's character Swann experienced when he tasted a madeleine cookie in "Remembrance of Things Past."

I gauge my progress towards my goal during chance encounters with the locals. Like the time when I am bicycling through a village in Rupganj area. A boy, barely ten, stops me, points to a tall Kamranga tree full of ripe juicy fruit, and offers to climb it and pick some, free of charge. "Want to try it, sir, it is very sweet", he asks me. I had forgotten how unbelievably hospitable, friendly and generous Bangladeshi villagers are. I realize that attaining this level of being Bangladeshi will be tough.

[Notes for non-Bangladeshi readers:

1. Bangladesh has 6 seasons: Summer, Rainy Season, Early Fall, Late Fall, Winter and Spring. In Bengali these are Grishho, Borsha, Shorot, Hemonto, Sheet, Boshonto. The language is Bengali (aka Bangla.)

2. Rajshahi in northern Bangladesh is famous for its sweet mangoes.

3. Shapla, a water-lily, is the national flower of Bangladesh.

4. Bangladeshi rickshaws have two brake handles but only one is attached to a (front) brake. There is no brake at the rear.

5. A hartal is political protest that shuts down shops and most traffic for the day. Offices usually remain open.

6. The Language Movement, from the 1950s, was a people’s movement in Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) to promote Bengali and resist the adoption of Urdu (spoken only in West Pakistan) as the national language.

7. Aalga Pechail means “unnecessary complicated talk” and Kora Misti means “very sweet” (used by fruitsellers.)

8. Shalik, bulbul, fingey and cheel are birds of sturnidae, nightingale, drongo and kite families.

9. Jibananda Das, a Bengali poet, is best-known for his celebration of natural beauty of the region.

10. You can reach Rupganj in an hour of bicycling from Dhaka’s diplomatic zone.

11. Kamranga is starfruit. LoTkon is a local fruit, intensely tangy with a nice flavor.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Old Dhaka Gems (Photos)

I am beginning to really like old Dhaka. The city reveals many gems once you look beneath the veneer of crowds and dirt. Like Rome, you might turn a corner and find yourself face to face with a really old building (ok, ok, so Roman buildings are a wee little bit older...)

Tara Masjid in Bangsal was the most exquisitely building I found. Parts of it are 200+ years old, though it was renovated in 1987. Here are three pictures of it.

Armenian Church goes back to 1781. It was built during Dhaka's heydays when many European merchants came here looking for business and their fortunes. It is locally known as "khristan bari". Here are three pictures.

Ruplal House is a grand 19th century mansion built by Mr Ruplal, a businessman. Today it houses some businesses as well as Army folks.

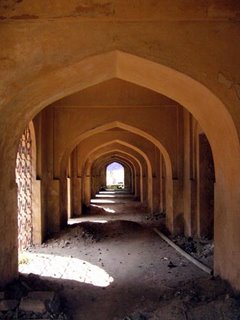

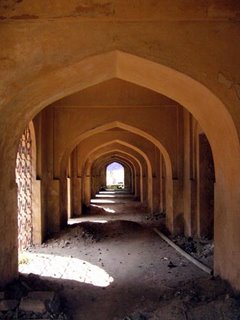

Khan Mohammed Mridha's mosque dates back to 1706. It is built on a raised platform. On the bottom floor, below the mosque platform, are dorm rooms where students live. The third picture is the hallway connecting these rooms.

Here are some pictures of Shakhari Patti. Shakharis are (Hindu) craftsmen who make ornaments from Shakha (conch shells). They came here over 300 years ago. This area is known for the very long and narrow houses (the second picture shows one such narrow house.) The third picture shows an abandoned building with the trademark triple-arch that is common to old Shakhari Patti houses.

A picture of Lalbagh Fort, which was built in 1678 by Prince Azam, the third son of Aurangzeb.

How can I not include the Pink Palace, aka Ahsan Manzil? Built in 1872 by Nawab Ahsanullah, renovated recently. I am not crazy about the color, but I am glad they put in the effort into renovation.

Tara Masjid in Bangsal was the most exquisitely building I found. Parts of it are 200+ years old, though it was renovated in 1987. Here are three pictures of it.

Armenian Church goes back to 1781. It was built during Dhaka's heydays when many European merchants came here looking for business and their fortunes. It is locally known as "khristan bari". Here are three pictures.

Ruplal House is a grand 19th century mansion built by Mr Ruplal, a businessman. Today it houses some businesses as well as Army folks.

Khan Mohammed Mridha's mosque dates back to 1706. It is built on a raised platform. On the bottom floor, below the mosque platform, are dorm rooms where students live. The third picture is the hallway connecting these rooms.

Here are some pictures of Shakhari Patti. Shakharis are (Hindu) craftsmen who make ornaments from Shakha (conch shells). They came here over 300 years ago. This area is known for the very long and narrow houses (the second picture shows one such narrow house.) The third picture shows an abandoned building with the trademark triple-arch that is common to old Shakhari Patti houses.

A picture of Lalbagh Fort, which was built in 1678 by Prince Azam, the third son of Aurangzeb.

How can I not include the Pink Palace, aka Ahsan Manzil? Built in 1872 by Nawab Ahsanullah, renovated recently. I am not crazy about the color, but I am glad they put in the effort into renovation.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)